This essay by author Jean Ciborowski Fahey, Ph. D. originally appeared in the CABE 2023 Edition of Multilingual Educator. Jean’s picture book I’ll Build You a Bookcase has been translated into Arabic, Mandarin, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

Jean Ciborowski Fahey is an author, parent educator, and speaker dedicated to promoting an early love of reading in children. She also consults for a variety of literacy initiatives and organizations and creates home literacy curriculum for parent-home visitors and early intervention specialists. She lives in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts with her husband, Tom, and dog, Indigo. Visit her online at readingfarm.net.

My story begins in mid-career: After testing thousands of schoolage children for reading problems, I became concerned about the many children we could not help. Brain scientists were discovering more about how the baby brain gets wired to learn to read. I saw that prevention of reading problems, at least for some of these children, was becoming possible.

I shifted my career focus from trying to fix the reading problems with students to preventing them with parents and caregivers. The science was pointing the way. If we were to reduce the number of children struggling with reading, we had to enroll parents and caregivers in building the foundation for reading as soon as babies come home from the hospital.

Guided by early literacy and brain science, I became a parent/teacher educator. In the process, I aimed to create a tool to help parents and caregivers better understand how to build a foundation for reading long before reading instruction occurs. My idea was to create a “once upon a time” bedtime story to teach parents how to put their babies on the path toward reading success. I was especially interested in reaching parents who were learning to read and/or learning English.

I wrote and self-published Make Time for Reading: A story guide for parents of babies and young children. I raised money on a web-based platform for a book publishing campaign and hired an illustrator (Peter J. Thornton), a book designer, and a printer. I turned what I knew about early literacy development into a rhymed story about how one little girl learns to read. As parents read and reread the story, they discover how back-and-forth conversations, reading aloud and often, and playing word and singing games are powerful ways to put babies and toddlers on the path toward reading success.

In 2016, I received a grant from the non-profit Mass Literacy to publish Make Time for Reading in a bilingual English/Spanish edition. I also won Toyota’s Teacher of the Year Award and published Make Time for Reading in a bilingual English/Portuguese edition. In my role as a parent/teacher educator and speaker, I sold 25,000 story guides to birthing hospitals and early education programs in greater New England over several years.

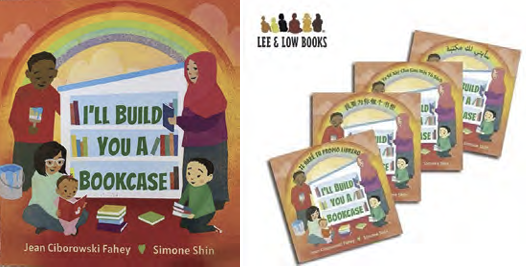

Hitting a home run: In 2019, I entered an international children’s story contest sponsored by the William Penn Foundation and OpenIDEO, an innovative design think tank. The mission was to write a 250-word story for babies and young toddlers while embedding parent messages showing how to help young children navigate the journey toward literacy. Having written my first book (Make Time for Reading), I was more than ready for the challenge. Among 500 entries from several continents, my story, I’ll Build You a Bookcase, won the $20,000 1st prize, and a publishing contract with Lee and Low Books in New York City—the country’s largest multicultural publisher. The publisher hired award-winning Simone Shin to illustrate the diversity in families and young children.

When the William Penn Foundation purchased 25,000 copies in bilingual Spanish, Vietnamese, Arabic, and Mandarin, I knew I had a new way to reach my audience.

According to Elliot Weinbaum, Chief Philanthropy Officer at the William Penn Foundation: “Talking and reading with children is how we lay the groundwork for strong readers in the future, even when it seems like they are too young to understand. This book seeks to engage children with its emotionally resonant writing and storyline while giving ideas to adults about how to support early language development. We are eager to share I’ll Build You a Bookcase with Philadelphia families, and we hope to see this book reach families around the country.”

One of our nation’s biggest challenges. The knowledge base that sourced both of my books comes from national literacy data that show the language and literacy gap between poor and non-poor children begins in infancy and widens significantly by kindergarten. This causes many children to fall behind in learning to read, from which they seldom catch up (Canfield et al, 2020). Most children’s journey to reading proficiency takes about nine years. By third grade (or by age 9 or 10), good readers make the transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” Referred to by reading researcher Keith Stanovitch as The Matthew Effect, the phrase comes from a paraphrase of the Gospel of Matthew: “The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.” (Stanovich, 1986) That is to say, the more children read, the better they read. As a result, their worlds expand, and indeed, for the children who love to read, life becomes extraordinarily altered.

Yet, for too many of our nation’s children, learning to read is difficult. Only 35% of our nation’s 4th graders are proficient readers, and low-income children are disproportionately numbered among poor readers (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2019) (The National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2019). Students who reach 4th grade without being able to transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” will struggle with social studies, history, and science textbooks (Ciborowski Fahey, 1994). This makes them less likely to graduate from high school on time, reducing their earning potential and competitive edge in a global economy. This also impacts their social and emotional development.

We now know a major culprit for low 3rd/4th–grade reading levels is that too many children enter kindergarten lacking the foundational experiences for learning to read. They fall behind in first and second grade and rarely catch up to their peers who have already learned to read for information, comfort, and enjoyment. We cannot wait until children enter kindergarten and hope for the best. Parents and caregivers are the strongest tools in the toolbox for setting children up for reading success.

Innovative solutions—start reading at birth. When we start reading to our babies as soon as we bring them home from the birthing hospital, we stimulate their brains while they are most malleable. Exciting new neuroimaging techniques reveal the parts of the brain that grow and develop in language and literacy-rich environments (Hutton, et al, 2021). Reading especially arouses the baby’s brain— and in a very particular region. In this area, the brain analyzes and stores the parts and patterns of the home language. Frequent reading, rhyming, and wordplay build the foundational experiences for learning to read.

Reading stories in the child’s home language can make a difference for both babies and parents. It makes sense then that baby books include the rhythm, repetition, and rhyme of the language spoken by the important people in the baby’s life. And because neural pathways in the baby brain form and strengthen through repetition, the more we read to babies and young toddlers, the more we prepare them for learning to read. And as picture books are often read over and over, they reinforce the parts and patterns of language so very interesting to the little listener.

Therefore, the more we read to young children before they can talk and walk, the more language they will hear. Hearing more language means learning more words. And learning more words before one can read will help children once they begin to read. And as for parents, a children’s story or narrative has a beginning, middle, and end, and illustrations that enhance the text. This can make the story’s messages more easily accessible to parents who are learning to read and/or learning English.

I’ll Build You a Bookcase appeals to a multicultural population. Using stories and art to teach parents to teach their children is an innovative way to reach families with babies. For almost two decades, I had the privilege of teaching expectant parents and parents of newborns how to put their babies on the path to reading success. I learned from experience that an easy-to-read children’s story can attract, inspire and educate parents of all educational and income levels, including parents learning English. And at the same time, designing children’s books that reflect the diversity of young, multiracial families who want the best for their children continues to be one of my life’s most gratifying journeys.

Winning a children’s manuscript contest gave me a coveted prize and a publishing contract. But more importantly, the contest gave me a platform to reach a diverse group of families with babies and young children ready for the extraordinary journey toward literacy.

“And then we can all read wherever we are, perhaps on a rainbow or riding a star. So let’s build a bookcase, and then we’ll build two—for nothing is better than reading with you.” —I’ll Build You a Bookcase, 2021, JC Fahey