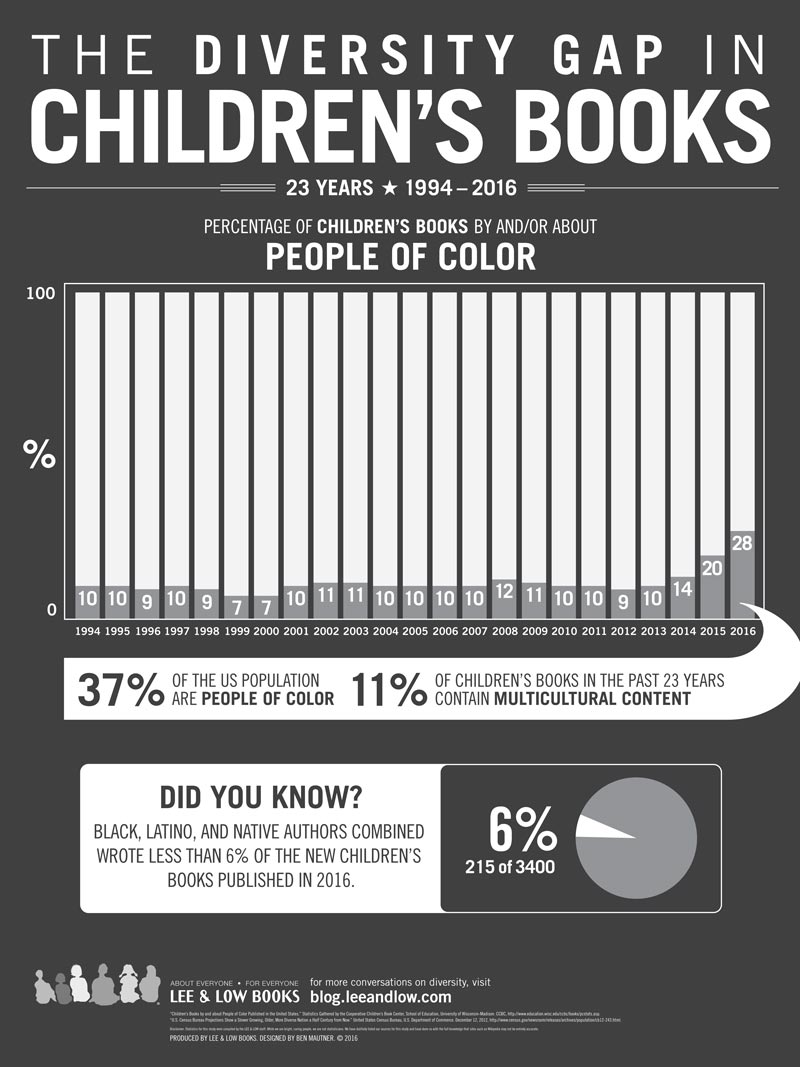

Last month, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) released its statistics on the number of children’s books by and about people of color published in 2016. Two years after the founding of We Need Diverse Books, the issue of diversity in children’s books continues to gain traction and media attention; it is the topic of panels, conferences, training sessions, and studies.

But is it all making a difference?

The answer is yes and no:

Holy heck, what an increase!

The number of diverse books being published each year stayed stagnant for more than two decades, but in 2014 it began increasing substantially. This year, the number jumped to 28% – the highest year on record since 1994 (and likely the highest year ever). 2016 also marked a number of important award wins for authors of color including a Caldecott Medal for Javaka Steptoe, a Caldecott Honor for Carole Boston Weatherford and R. Gregory Christie, a Newbery Honor for Ashley Bryan, and a Printz Award and Sibert Medal for Representative John Lewis.

But wait…

While the number of diverse books has increased substantially, the number of books written by people of color has not kept pace. In fact, in 2016, Black, Latinx, and Native authors combined wrote just 6% of new children’s books published. In other words, while the number of books with diverse content increases, the majority of those books are still written by white authors. We wrote about this phenomenon back in 2015, and the numbers haven’t changed much since then.

KT Horning delves into the data to look specifically at the consistent lack of representation for Black writers:

We can see that there are a whole lot of books being written about African Americans these days by people who are not African American. Does it matter? It certainly can. Especially when you care about authenticity.And, more significantly, this means we are not seeing African-American authors and artists being given the same opportunities to tell their own stories. In fact, last year just 71 of the 278 (25.5%) books about African-Americans were actually written and/or illustrated by African Americans.

Where do we go from here?

This year, the data includes some things to celebrate, and we should celebrate them! It’s amazing that in just a few years, the number of diverse books published has increased so substantially. Fighting for representation is hard and often thankless work, and it’s easy to become burnt out or pessimistic about the possibility of change. These numbers are a testament to those whose groundbreaking work has paved the way for more diversity and equity in publishing, people like Walter Dean Myers, Rudine Sims Bishop, and Debbie Reese. Change comes slowly, but the numbers tell us that it does indeed come.

At the same time, the numbers leave us with some questions that publishing as an industry must answer:

Why are we giving preference to white authors telling diverse stories rather than authors of color/Native authors?

Why are Black authors and illustrators still so underrepresented?

Since publishing is still largely white, what training are staff receiving to help them publish the increasing number of diverse stories with cultural awareness?

Until publishing answers these questions, the improving numbers will tell just part of the story.

Thank you for this update. Very interesting to see the slow progress. But I’m surprised to see how many books are published about children of color that are written by white authors. We have so much work to do.

I agree….

Very interesting and informative article. Some change is better than no change certainly holds true here. Yet, there is room for more. I would be curious to hear what causes that gap. Why are works submitted by African American authors being turned down? I know of African American authors (to include myself) that submit high quality manuscripts to publishers and enter contest but is never considered. At an event sponsored by a popular children’s book organization the facilitator went as far as to suggest that I submit the work that was critiqued that day to a well known African American publisher. My curiosity has been more than aroused in this area.

J.P., I don’t think you have a clue of how hard it is to get a children’s manuscript accepted for publication by a legit publisher no matter what color you are. Many publishers won’t take unsolicited submissions, or unagented submission. Therefore you must go through an agent, which winnows down the number of submissions significantly. Then, even if you do have an agent, even niche publishers get 40, 50, or 100 submitted projects for each one they decide to publish.

You have a better chance of hitting one number at the roulette table in Biloxi or Las Vegas than you do of getting your book published, no matter who you are. Let’s just celebrate all the progress that has been made with diverse books. Children’s books now look like America. It’s victory, and I don’t know why there isn’t more celebration.

Can we also ask the question, “Where is the diversity when it comes to librarians?” Librarians choose what books children are exposed to. We advocate, place on shelves, make purchases and book trailers, and gain the interest in reading. Ideally, the love of reading should inspire regardless of race. But let’s get real, a black librarian has more influence over what a black child may choose to read than any other race (assimilation, authenticity, alikeness in more than just skin tone). Just as the reflection in books matters, so does the reflection in the advocate. Investigate the numbers: http://bit.ly/2olQc4U. There’s a decline in African American Librarians. 89% of librarians are white with 4.5% black, 3% Latino, 1.4% Native and 2.7% Asian Pacific Islanders (ALA Member Demographic, 2006). Where is the challenge to address that? Why am I shunned and excluded from the predominantly white groups because I “always address diversity?” Why am I looked at like I just stepped off of the “Library UFO” when I present at conferences? But I will say, at my last conference, I was thanked because it was the first and only time they saw a black librarian presenting. Also, as a black librarian, our kids are past books about ancestors and their plights as slaves or activists. Our mental trap and representation of books about these two subjects (enslavement and fighting for rights) are important, but also “played out” in a sense that our kids aren’t rushing to read/buy books about it. How about publishers promote/award books like “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas or “All American Boys” by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely..dare I mention “Ink and Ashes” by Valynne Maetani? Librarians, book reviewers and bloggers (aside fromt the usual white favorites) all need a dose of diversity, as they’re all apart of the web we weave!

I am a biracial former librarian who left the library profession ( I’ve since re-entered, but as an adjunct a library school, not in an actual library). Part of the reason I left was because it is such a non-diverse field, and I realize leaving doesn’t “help,” but I couldn’t stand anymore being the “diverse person.” One of the reasons I think so many librarians of color leave is that LIS education and professional development has a block when it comes to diversity, in that they don’t understand that presence is not equity and that diversity scholarships and the like, while commendable for their efforts and philosophy, don’t do anything if the rest of the profession isn’t charged with changing their attitudes and outlook. One of the things I really disliked about my MLS program and many others, and something I try to address in the classes I teach, is that anytime Those People are mentioned to acknowledged or classes are taught about serving immigrants, the poor, the incarcerated, or whatever other marginalized group, they are electives, not required, and they’re also seen as being adequate and reason enough to exclude those perspectives or issues from being touched upon in “regular” classes. LIS as an institution will never improve so long as that is the case.

BSP: this forthcoming book may be of interest to you: http://libraryjuicepress.com/whiteness.php

“mentioned OR acknowledged,” not TO. Typo.

I am in library school at the moment and am White, but I feel you. Pretty frustrated that there’s nothing required on all the populations you mention above. (We don’t live in an all white world; come on!)

K.T. Horning, at her interview the other day at Hornbook, was even more specific about American publishing. I commented there, and cross-post here, because taking these numbers on their face and comparing them to the 2010 USA census is telling.

Number of picture books in the USA about people: 511.

Number of them about white people: 319.

Percentage of them about white people: 62.4%. (conversely, 37.6% are about non-whites, higher than the numbers you cite above).

Percentage of the USA population that is white, according to 2010 census statistics: 63.7%.

Percentage about Asians and Asian-American: 5.8%.

Percentage of USA population that is Asian: 3.6%

Whites slightly underrepresented on percentage basis, Asians over-represented. African-Americans underrepresented, but the CCBC’s new “multicultural” category (better, non-designated non-white, since many multicultural children are white in color but non-dominant culture in culture) may skew the percentage for non-whites, since it has almost 11.5% of all books about people in it.

Here is K.T.’s count…

511 picture books about people (U.S. publishers only)

White: 319

Multicultural: 59

African American: 46

Brown-skinned: 42

Asian/Asian American: 30

Latinx: 20

Biracial: 10

Native American: 2

***

As for books being written about groups by people not in those groups, it’s an issue only if members of those groups are being turned down by publishers at a higher rate than those of the dominant culture. If the opportunity rate for white writers is e.g. 14 writers being turned down for each writer whose manuscript accepted, and the opportunity rate for e.g. African-American writers is 10 rejected writers for each writer’s manuscript accepted, African-Americans have a better chance of getting their work published than whites. And vice-versa.

If you’ve got statistics like this from Lee and Low, can you share?

A minor correction. I referred to the Multicultural category and count of 59 books where I should have referred to the CCBC Brown-skinned count of 42 books.The Brown-skinned count is 8.2 percent of all books. If just half of the Brown-skinned count (21 books) is added to the African-American count of 46, it totals 67 out of 511 books, or 13.1% of all children’s books about people published in American. The 2010 census count for African-Americans has them at 12.3% of the population. It’s slightly over proportional. Brown-skinned could of course refer to everything from African to African-American to Cuban to Anguillan to North African to many who live in the Middle East.

This is such a great and informative blog! I had no idea numbers of authors in non-white cultures were so low in children’s publishing. Thank you for trying to improve awareness of this deficit in publishing, and for asking the difficult questions. We should absolutely be working to put in place assistance in publishing non-white views and books. And while we should be working towards this, there are always multiple aspects to work from e.g. promoting cultural works in libraries and schools to improve diversity amongst our youth. I was also not aware that a fair amount of the cultural books available were written by authors from another culture, and the authenticity issues this has wielded are not without worry. I especially praise you for including a ‘Where do we go from here?’ finish, leaving us to think about how culture diversity in children’s publishing can be lifted from underrepresentation.

I just reached out to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, to see if I could obtain the list of just the book written by or about African-Americans they report 93 children’s book written by African Americans. That number seems awfully low. Surely more than 93 children’s books written by African Americans and featuring African American characters were published.

I wonder if the CCBC is simply missing a segment of the books being published. They say, “…the CCBC receives most of the trade books published annually in the United States.” If I can look at the data I’ll be able to tell.

A few quick queries against Ingrum’s database is even less encouraging…

Thank you to the person who posted those stats. I think another important thing to consider is that fact that I’d say the majority of published authors and illustrators have some form of college education (I could be wrong – is there a poll out there for that?) If you look at statistics by race you’ll see that while minority groups like Asians have a high level of education, African Americans are at the bottom. The African American population also has the highest amount of poverty. So… why is there a gap? This could certainly be why. If we want more African Americans (and other groups) writing books then we need to fix the education system. Easier said than done.

It depends, but English and Literature are not often favored subjects of AA children and people. Many children are peer pressured to conform to incorrect grammar and English, sometimes bullied, ostracized, or beaten by their peers if they speak and write correctly. This poses extra barriers to developing high-level writing skills and is something to take into account as to why there are a lot less pro-level AA writers with the skills necessary to be published. But there’s an upside in publishing within the last few years now. The mostly white (and sometimes exploitative) publishing houses’ staffers demands for even more POC characters and authors gives some AA authors a much higher consideration even when works are substandard, they will work with and even assign entire teams to tear apart and reform and help authors rewrite manuscripts if necessary and the idea is good (this is rarely the case for non-AA writers even those in other POC and other diverse categories, it’s the executed skills that matter versus ideas which were formerly considered a dime a dozen). I’ve witnessed AA authors of all level of skills given a greater chance and given more leniency than others with the exception of white men who are still dominating at least in adult genre.

To Erin McKenna–Yes, the education system needs to be fixed but more needs to be done. If you look at all of history especially countries that have a history of slavery/racism/discrimination/oppression for centuries factors into why blacks are at the bottom and are very poor compared to whites, Asians, etc. Black women are increasingly becoming more educated and owning their own businesses compared to other groups because for so long they couldn’t. It’s not so easy just fixing an education system. It’s very hard to correct 400 plus years of racism, discrimination, oppression, sexism, etc. along with the horrible education system. Blacks are disproportionately affected by 400 plus years of everything that I mentioned above. That has set back the black race for over 400 plus years. Since whites, Asians, etc. didn’t have to deal with all of that and still don’t–it’s not surprising at all. I wonder if blacks had started off on the same level playing field as whites then this wouldn’t be a discussion at all. If whites, Asians, etc. had to deal with all of that for 400 plus years worldwide then they wouldn’t be where they are today. Who would?

I forgot to mention that Nigerians are the most educated over the whites and Asians too. Somehow, nobody ever mentions this. Lately, there are more publishers willing to publish more books from Africans compared to African Americans.